Hello, my friends,

I’m writing this on the day I turn 39-years-old. I told Ashley this evening that I’m turning the big 4-0 next year and she wasn’t convinced. We had to take a moment to determine whether it was really true (it was). Mostly it’s just that I don’t think about my age that often. I do perceive change: My hair has taken to growing upside down (what was formally at the top of my head is now coming out of my nose), heartburn is more frequent, and names I haven’t thought of in a while along with the random words occasionally elude me. These are real, but I don’t associate them with any particular number and, more importantly, I don’t worry about them too much. So, yes, I’m turning 40 next year but it’s not really the big four-oh, it’s a year like any year and I’ll be 41 on the following year. Meanwhile, life happens, which is as much as I ask for myself. More life, please, Mr. Waiter…And bring enough to share.

Reading (Abstract) Poetry Out Loud For An Audience

Many years ago, I was a young imposter at a very talented writers group. One evening, after pasta, I read a poem that could either be described as abstract or, more vividly, as a fever dream assemblage. It started:

I’ve drafted my eyesore lariat: proctor-band, wise-lad cover-all demerit, with a sink-hole, middle-laden, lasso on a pulse-beam pulling Santa with a satellite;

(the entire poem is here)

I don’t recall how it was received as a whole but I do remember that one of the group members, an actress, suggested that to improve my reading I go through the poem and consider the emotional value of each line (maybe she said each word, I’m not sure). We made vague plans to get together and do this but it never happened. Her relatively simple advice stuck with me though, and I’ve thought about it occasionally over the years including while I was preparing for the poetry reading I was part of this past Friday.

If you’ve gone to poetry readings with any regularity, you know that poets tend not to be the most entertaining performers. While reading styles range from the declamatory style of old to the consciously performative way of slam poets, most tend toward the former, seemingly eschewing the techniques of expression deliberately by reading their work in flat tones and slowly, oh so slowly. I don’t think most poets intend to sedate their audience, but that is what happens to humans when they are faced with bouts of long, toneless, rhythmic (or not) recitation. Or maybe it’s just me?

I presume that the reading pace is intended to be an aid to understanding the poems. After all, poetry as a genre (beyond slam poetry or teenage journal poems) tends to be fairly information dense. The depth of meaning, already a challenge, is further occluded by esoteric word choices (like “occluded”!) and obscure references forcing readers to study first then enjoy, if it gets to that. My experiences at past poetry readings have shown that even when read at a glacial pace, there’s really no point in speaking academic poetry aloud to an audience. Except, that is, if the reader uses their expressive power to open up a path to meaning.

When I refer to this “path to meaning” (a non-technical term), what comes to mind as a prime example is the mounting of Shakespeare plays. Depending on the quality of the performers, Shakespeare’s language can be made to feel as hard as concrete to no more challenging than conversational English; an actor’s gestures, intonation, volume, and facial expressions make all the difference. Sometimes it’s not even the words that matter. I once watched a performance of Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros put on by the Le Cercle Francophone at UCLA. Though the show was completely in French, meaning I understood practically none of it, I remained entertained throughout! Can this effect be achieved with poetry?

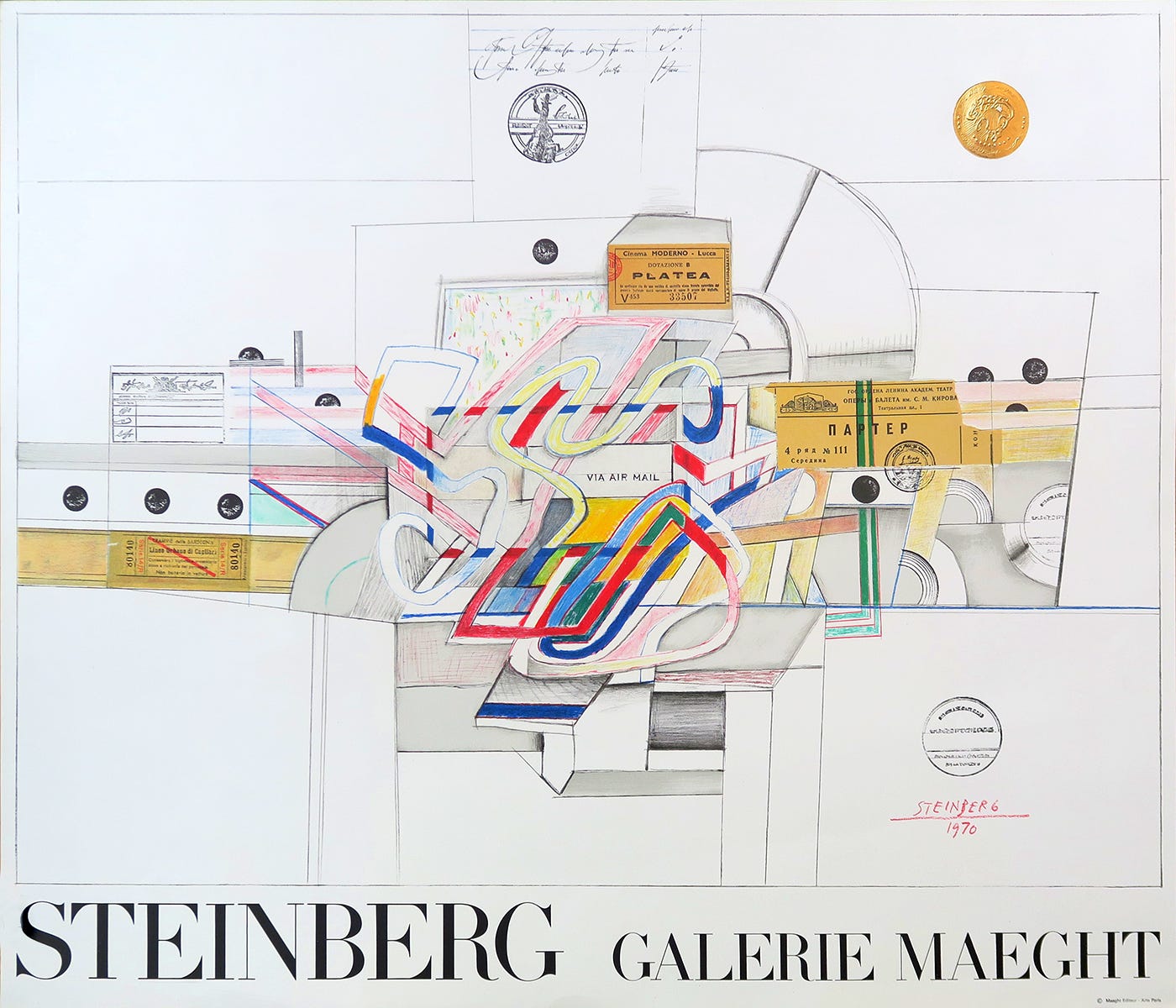

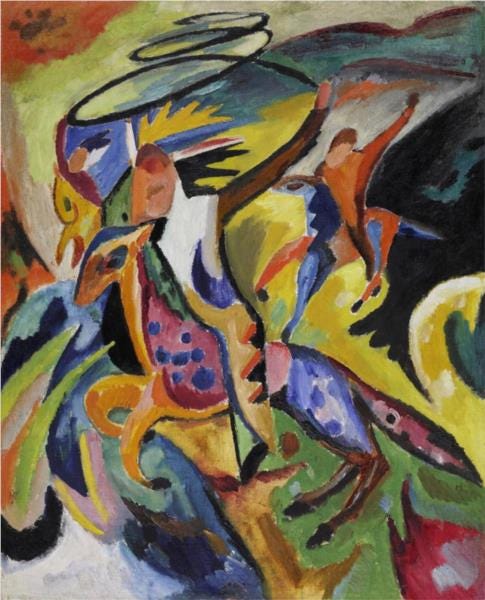

The question occurs to me because a portion of my ouevre, as with “Diary Entry — 20 April 2008” above, doesn’t signify in a straightforward manner. It’s visual equivalent might be something like the works of Cubist painter Lyubov Popova or Saul Steinberg’s collages, fugues of clashing sense and non-sense. In their medium, we evaluate colors, shapes, texture, and material in parallel to questions like “How does it make me feel?” or “What are the meaningful elements here?” A glimpse of these works is enough to slap away silly questions like “What is it?” or “What does it mean?” (“How does it mean?” is maybe better?). Yet, poetry doesn’t afford readers such an instantaneous mode of evaluation — visually, most poetry looks relatively similar.

So, you start reading (or listening) to poetry and your orientation takes place in the first few lines. If you’re a square, you’ll read the lines of my poem above and quickly conclude: “Oh, I see. This is bullshit.” And who am I to argue with something that’s purely a matter of taste? The modernist shift that partially off-loaded sense-making from the artwork to the viewer isn’t everyone’s drug of choice (realism, after all, is alive and well). But is this a fact that poets who work in an abstract mode must accept? That their less “grippable” poems won’t work with audiences? I’d like to think that, for those poets who are skilled readers, there is a way out.

Slam poetry is entertaining and communicative partially because it is composed to be performed — and understood — by audiences. The poem I linked above (where it says “consciously performative”), Shihan’s “This Type Love” is immediately comprehensible: The narrator is describing a sublime feeling of love that he’d like to have. What’s special is not the meaning itself — which is not complicated — but the multiple clever ways he tells us about it. Though the text of the poem lends itself to be spoken, that's not enough. They key is that Shihan performs the crap out of it. He kills it!

Academic poetry (what I’m using imperfectly and maybe inappropriately as a stand-in) is the opposite of slam poetry in that the meaning is often so, so special — a take on the underside of a literary moment only three people know about — but the way of expressing it is not outwardly clever. If the reader doesn’t connect with a far-off reference, for example, a whole line (maybe the whole poem) is lost. An expressionless reader buries it deeper. My response to hearing this sort of (free) verse is typically, “I guess I’m not smart enough for this” and move on with my evening.

If that’s an acceptable audience reaction for those poets, then they should stay the course. After reflecting on my own reading this past Friday (where I did read one whiny abstract poem), I realized that I need to do better at coloring my readings. This is especially true since unlike the two example genre mentioned above, my “avante-garde” poems don’t have any meaning in the conventional sense, at least not meaning that can be easily described in the conventional ways. My challenge, then, is set. Last week, I asked “How would I build a bigger audience for my poetry anyway?” One way is to give effective readings.

The most gauche way to define what is effective here would be to reduce it to a transactional behavior: If an audience member purchases a zine or book, gets on my mailing list, or slips $100 dollars into my pocket, then the reading was short-term effective. If they write their dissertation on my poem, make a documentary about me, or rename their children (and maybe themselves) Olegkagan, then that means it was long-term effective. By the time I die, my legacy will be measured by the amount of Olegkagans spotting the Earth.

So, finally, how to do it? I’ve been talking about it the whole time, I think. We poets have to be more conscious and intentional about how our reading will affect the audience. So before every performance, we have to answer the question: How do we want our audience to feel at the end? Since we’re limited by our output — we write what we write — we must curate our poems (and those of others if we’re including other people’s poems in our performance) to create a trajectory towards our response to the first question; comedians structure their set, and so should poets. Everything around the poems (the introduction to the reading, to the poems themselves, and concluding remarks) should aim in the intended direction. And finally finally, the poems themselves.

Returning to the advice I received all those years ago: Each line should be imbued with specific and unique expression. To our advantage, the human span of emotion is huge. Though we’re certainly not all skilled actors, putting even some effort in using acting techniques to get at the essential in each line would be worthwhile. Memorizing the poems will be helpful, too. There’s a freedom in reciting that isn’t there with reading, plus, without the paper, you regain use of your eyes and hands.

After the reading last week, I told Ashley that I had the urge to go out and read more — at open mics, readings, etc. I need to hold myself to that once every month or two months. Without actually putting these thoughts into practice, there will have been no point in any of this rambling, much less sharing my “eyesore lariat” with you.

In honor of your poetry, I shall adopt three children and name them Olegkagan, Kaganoleg, and O-Kag. O-Kag will be the cool, rebellious one.