Hello, my friends,

Happy Thanksgiving! The ongoing sumo tournament is entertaining as always (though my favorite, Takakeisho, will not win), my basil plants are sprouting new leaves, and I got a full night of sleep Wednesday-Thursday night! These are just a few of the many things I have to be grateful for. And you?

Mini ‘Views

As mentioned a couple of weeks ago (#37), I’ve been in a graphic novel mood. Since then I’ve read a few more and am keen to share my opinion of them with you:

The Eight-Fold Path by Charles Johnson and Steven Barnes: An assemblage of stories in wildly different genre pointing to the Buddhist Eight-Fold Path. While some of the stories were individually effective, they did not make up a greater whole at least partially due to the forgettable framing story.

Achewood: The Great Outdoor Fight by Chris Onstad: An omnibus of the Achewood webcomic going all in on a fictional “Great Outdoor Fight,” an event where people from the world over come to central California to duke it out. I say fictional specifically because everything about the book (including the ads on the end paper, a list of past winners, and an entire backstory in the appendix) gives the Great Outdoor Fight a strong sense of reality. The story itself centers on protagonist Ray (a dog…all the characters are animals) enters the Fight. It’s weird and amusing, and would have been all the more so had I already been a reader of Achewood.

Liebestrasse by Greg Lockard, Tim Fish, Héctor Barros, Lucas Gattoni: The tale of a short but meaningful romance between two men, a young American banker and a German art dealer, at the very end of Weimer-era Germany. I liked the thick lines on otherwise realistic art, fashionable period-appropriate suits, and the portrayal of the Nazi rise moving from background annoyance to ignore to engine propelling the entire plot.

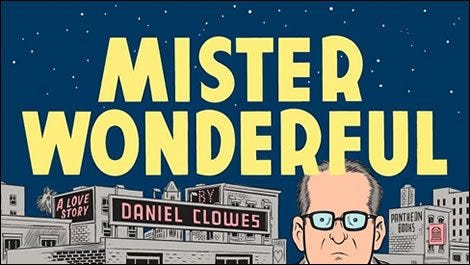

Mister Wonderful: A Love Story by Daniel Clowes: The very beginning of a relationship between a pair of divorced introverts. While every facial expression in the book reflects some sort of suffering (even the smiles), the main character’s inner monologue is even more self-deprecating! The dialogue — including how that inner monologue is overlaid on the actual speech — in Mister Wonderful really keeps things moving. Not only an entertaining read, but also a clinic on visual storytelling.

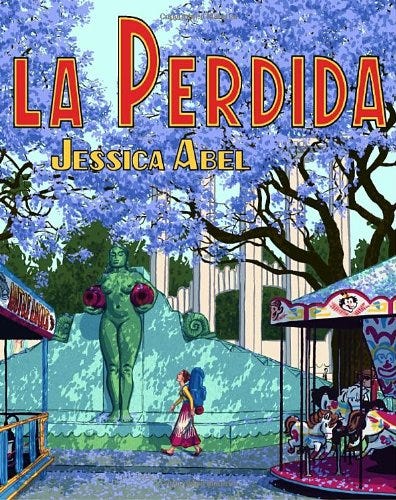

La Perdida by Jessica Abel: A naive young lady moves to Mexico City with nary a plan in mind and, of course, gets in over her head barely making it out alive. Each frame has multiple levels of understanding belying the author’s insight into every character’s world: The innocent Carla, her street-smart (and street-dumb) but unworldly local friends, long-term members of the ex-pat community, the outside world, etc. The sense of authenticity in La Perdida gave me a feeling of dissonance: Is it a memoir? It has to be a memoir! (It’s not). This book should be part of a class on cultural competence along with New Kid by Jerry Craft.

Robert Moses: The Master Builder of New York City by Pierre Christin and Olivier Balez: A stylish biography of the all-powerful shaper of New York that had trouble deciding what about Moses was most important. Many aspects of Moses’s life were obliquely referred to in short scenes while others, his battle with Jane Jacobs was a whole chapter. What the authors did well was demonstrate the subject’s importance at it’s height followed by its gradual decline. I would have loved to learn more about the machinations that got Moses to his pinnacle, like the sneak peek I got reading Working by the heralded Robert Moses biographer Robert Caro.

Whoops, I tried to keep them slim, but I guess some of the reviews gained a little weight. #SorryNotSorry #ThanksgivingDinner

TraumaGate

In casual conversation, I learned that one of my fellow exhibitors at a library outreach event this past Saturday has a five-month-old son, his first. After the typical orienting questions — how’s the baby sleeping, eating, pooping, smiling, etc. — we began talking about breastfeeding and other occasionally contentious topics. I quickly assured him that I’m neutral on most subjects related to other people’s parenting choices. Breast milk or formula? Don’t care. Co-sleeping or crib? Your choice. Sleep training? Introducing food? Bundling babies as if they’re in Antarctica? Shrug from me. Sure, I have opinions about those things, but I don’t share them unless asked directly. As with baby clothes, the world has a major surplus of unsolicited parenting advice! That said, there are a few morsels I offer to new parents:

Whatever challenge you or the baby are going through now, it’ll be over in like a week; everything is a phase.

Infants cry all the damn time and it can drive parents crazy, so if you’re on the toilet or eating toast or just looking out the window and having a breather, you don’t need to drop everything and rush to save the child the moment they start hollering. The earth will keep turning for the next five minutes despite the poop in Young Mister’s nappy. I summarize this with a morbid little quip: “Crying, not dying.”

Similarly, babies fall off couches, toddlers bump their heads, and adults worry. You can relax, they’re fine. It’s a scientific fact that babies are made of jello! Very hardy jello.

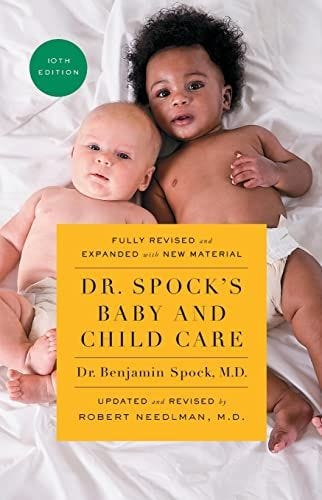

Most important is the general attitude of my favorite parenting book, Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care, 10th edition. This is not a direct quote but it summarizes an idea that was vital to me during my new dad doldrums (“dadrums”?): New parents have everything they need to do a good job. You can look things up online (though for less contradictory advice, I recommend Spock) but for the most part just trust your instincts. The great majority of indigestion and rashes that alarm new parents are nothing to worry about. You got this!

More to the point, there are few normal parenting decisions you can make that will “traumatize” your child. I wrote last week about Sophie’s getting out of bed. Part of me is ambivalent about putting a gate on her door because who wants to cage their child? But the fact is that putting a gate on Michael’s door in his second year allowed us to keep our sanity. Surely, he didn’t like it. Tried to break it (actually did a few times because he’s wily and strong), and would occasionally fell asleep next to it. And doesn’t it sound horrid when I characterize it as “caging” a child?

It’s so easy to dramatize relatively mundane choices. And mundane they are. Do you know how I know? Michael and I were recently chatting about the gate that I’m going to install on Sophie’s door (I changed her door knobs a few days ago so it would fit) and when I asked him if he remembered the gate on his door, I’m pretty sure he had little to no major recollection of it. This from a child who remembers a random joke I told off-hand like eight months ago.

So, in conclusion. You know what traumatizes kids? Beating, gaslighting, or ignoring them for hours at a time. You know what doesn’t? Formula and baby gates.

Thank you, Critics

I’m in the middle of listening to the audiobook of The Sweet Science by A.J. Liebling, a book of post-WWII-era boxing essays that feel like accompanying an intelligent and entertaining pal to the fights, followed by a drink or three. David Remnick of the New Yorker (where Liebling wrote as well) said in 2004 essay, “In The Sweet Science—in all his books—Liebling himself, the voice and the character, is immensely appealing: he is boundlessly curious, a listener, a boulevardier, a man of appetites and sympathy. He is erudite in an unsystematic, wised-up sort of way. His sentences are snaky and digressive, and thrive on the talk of the Times Square gyms and cigar stores.” Aside from writing about boxing and French food, Liebling also spent time as a critic of the press. An ironic role for a journalist, skewering your colleagues.

The role of the critic in the greater society is ambivalent. Critics have been characterized at various times as untalented parasites while simultaneously lauded as luminaries as we’ve seen with the likes of Roger Ebert, Jonathon Gold (here in Los Angeles, particularly), and anyone who reviews poetry for tiny literary journals. Regarding the latter, anyone who doesn’t see the nobility in such selfless exertion is a heartless cretin. And, of course, since the rise of Web 2.0 in the early 2000s the dismissive “Everyone’s a critic!” has become a simple reality.

Well, I dissent! While many can criticize, not everyone is a critic. The excellent exemplar of that age-old trade combines expertise, opinion, and expression. Roger Ebert was a cinephile; his reviews made it clear that he had seen and established a defensible point-of-view concerning the world of film. Moreover, like Liebling, he expressed that perspective in voice that cinefans appreciated. Compare Ebert with the average Yelp reviewer: Everything one needs to know is in the oft-used phrase “not worth the price” as seen in reviews of anyplace from Denny’s to a Michelin-starred restaurants, the obsession with authenticity (particularly in relation to purveyors of international cuisine), and the appearance of that meaningless word “quite.”

Good critics are rare. But the appeal of their work ignores the passage of time and subject matter interest of the reader. I’m fairly certain that I would happily spend ten minutes reading about the fishtanks of the 1930s were the piece written by a skilled critic. So, on this Thanksgiving edition of HMF, I say: Thank you, critics. Even when you’re wrong, you do it in style.

“Crying, not dying.”

Laconic wisdom.

But this is not a haiku.